What do puzzles from magazines of the 90s and modern I Spy games have in common? What is the success formula for hidden object games, and how to create an interesting product in an unpopular genre? Let’s find that out.

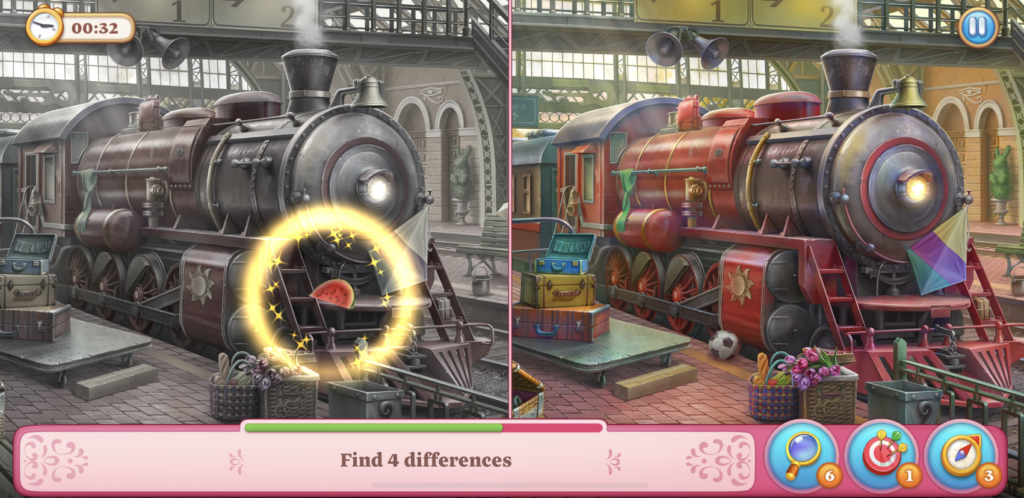

HOPA games (hidden object puzzle adventure) are casual games in which the player looks for hidden objects. The list of objects is presented in words, silhouettes, and anagrams, limiting the time to complete the level and complicating the process in various ways.

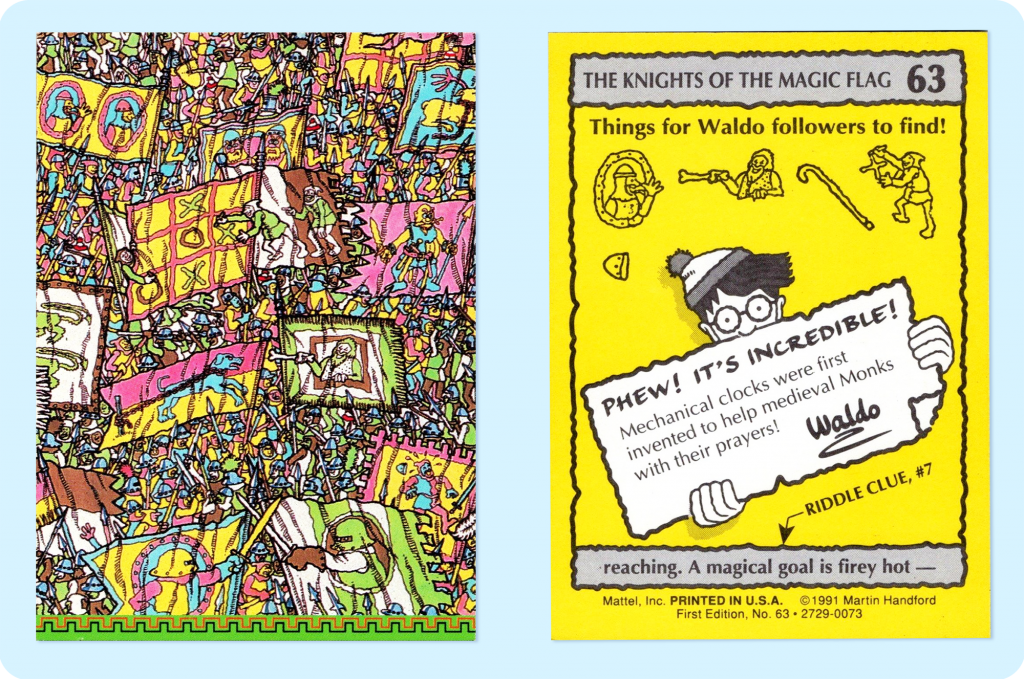

The original prototypes of casual I Spy games were in old magazines. The entertaining sections like Spot the Difference and Find 10 Objects are the progenitors of modern puzzles. Some will remember a series of magazines with colorful I Spy spreads. They featured Waldo, a guy in glasses and a red and white striped sweater, who hid in a large crowd of people and objects. There were also wimmelbooks, in which each illustration is a search scene.

Where’s Waldo? The Fantastic Journey (Book 3)

At first, computer games used only basic mechanics in the hidden object genre – the search for objects and differences. One such HOG pioneer, Alice: An Interactive Museum, was created for Windows 3.x in 1991. The universe created by Lewis Carroll inspired the plot. The player walks around the 12 mysterious rooms of the mansion, collects 53 cards from the deck, and deciphers the clues to complete the game. The game’s navigation utilizes the mouse: the player clicks (often at random) on various objects, finds hidden cards, and moves on. Despite the sometimes frightening graphics and sounds, the game turned out to be very atmospheric and interactive.

The first major casual game developer to make headway in the hidden object genre was Big Fish Games. The popular Hidden Expedition series includes as many as 17 games. Starting with the computer game Hidden Expedition: Titanic, they captivated thousands of fans, and their follow-up game in the series, Hidden Expedition: Everest, was released for the iPhone.

It’s enough to know a couple of facts when understanding the scale of creating a hidden object game. Big Fish Games recruited the world-famous climber Edmund Viesturs as a consultant. They made him the main character of the game Hidden Expedition: Everest. And National Geographic was chosen as an information partner and supplier of photos and videos.

While the first hidden object games were essentially adaptations of paper puzzles to find hidden objects and differences in pictures, the modern HOG games boast a variety of mechanics and a well-thought-out plot. In such quests, users are looking for not just a clicker game but also a fascinating story.

Therefore, modern developers will season their search sections with an interesting plot, mystery, colorful characters, humor, lively dialogue, and exciting cutscenes. This approach works not only to attract but also to retain the player. With each plot twist, the player is more involved in the process and history and more willing to return to the game.

I Spy games include the following elements and features:

A lot of work is required to make your hidden object game exciting, original, and, at the same time, popular for a long time. Therefore, the first item in the plan for creating a cool HOG project by VOKI Games was a large-scale study.

Based on its results, we determined the success factors of I Spy games:

Since the essence of hidden object games is to search, we focused on the quality of hidden locations.

The idea behind each hidden object location in the game is carefully crafted to match the setting, theme of the game, or specific event (when it’s a seasonal or holiday update). The appearance of a new search scene should be logical: in a historical museum, there is the exposition of a politician’s office, and in an abandoned hotel, there is a cobwebbed room.

In the second stage, we collect a folder with photographs of premises and individual objects, which we take as an example when developing a new location. It is important not to forget that the future interior should match the atmosphere of the game, the visual style of the main art, and the era in which the game events occur.

Inspired by the references, the artists create sketches of the future search scene. The goal is to draw multiple variations (often in black and white). The lead artists review the resulting sketches, and they choose one that is the most functional and meets the requirements. Next, we detail the final sketch, think out the lighting, and work on the perspective.

At the 3D modeling stage, the sketch is handed over to a 3D artist who makes the location three-dimensional. We consider the objects’ real proportions so that the picture looks natural. As a result of modeling, we get a voluminous, detailed search scene.

At the stage of 2D processing, we detail textures, improve perspective realism, lighten up overly dark areas, and touch up the image. The task is to bring the design of the hidden location to absolute unity with the visual style and atmosphere of the game. After that, we begin to animate locations.

The animating factor creates an atmosphere. It’s important not to overdo it and not to draw too much of the player’s attention to moving objects. It’s enough for the animator to add smooth movements. Think of a gently swaying branch in the window if we are talking about a room, and in the case of a sea location, a couple of sparkling reflections on the water’s surface.

At this stage, we introduce hidden objects into the location. It’s important to consider the size of each object and its placement, ensure that all areas are adequately lit, and take into account that the game can be launched at a low display brightness.

It’s also important to hide the item so that most of it is visible. An example of unsuccessful objectification is a fallen globe that lies behind a cabinet, and the player sees only its stand.

Players appreciate the creative approach to placing such objects. Let’s say our task is to hide the family coat of arms in the living room of the palace. Instead of simply hanging it on the wall, we can sew it with gold thread onto one of the sofa cushions. The player will not discover the emblem immediately, but such a find will heat up their interest in the gameplay.

At this stage, the search scene is filled with music and sounds. Ambient sounds play in the hidden location to enliven the result. For example, this may be a ticking clock hanging on the wall or the quiet crackle of logs. This technique creates the atmosphere.

After taking all the steps mentioned earlier, the programmers introduce the location into the game. The result is tested, re-checked for display quality on different devices, and prepared for release.

This is such a complex and fascinating path that the team goes through when preparing each search scene. If you’re as enthusiastic about creating hidden object games as we are and want to dive into game development, make sure to have a look at our Vacancies section.